For foreign ecommerce merchants selling to U.S. customers, the trade landscape has shifted dramatically. Recent U.S. policy changes are ending the long-standing de minimis exemption on low-value imports and doubling down on tariffs – especially for goods made in China. The result is a “new normal” of no duty-free threshold, persistent import tariffs, and full customs entries, forcing brands to rethink their cross-border strategies. This article explores how brands can manage the impact of these changes. We’ll clarify what the end of de minimis means, why tariffs aren’t going away, and how correct customs valuation and compliant planning are now more important than ever.

The End of U.S. De Minimis (Low-Value Exemption)

On May 2, 2025, the United States eliminated its $800 de minimis duty exemption for goods made in China and Hong Kong. This means that all shipments from those locations, regardless of value, now require a full customs entry and are subject to duties and fees. Brands should not assume it stops there. U.S. officials have signaled plans to lower or eliminate the $800 de minimis for all countries in the near future. In fact, many trade experts anticipate full removal of de minimis for all origins by the end of 2025. Merchants must prepare for a world where every cross-border package could incur duties and require a full customs clearance, no matter how small.

Tariffs Persist – Plan for a 10%+ Import Tariff as the New Normal

Compounding the challenge, U.S. tariffs on imported goods are here to stay. Once implemented, tariffs are challenging to remove. Take the Section 301 “trade remedy” tariffs implemented in 2018 during Trump’s first term. They were kept in place and even expanded under the Biden Administration. Merchants hoping these tariffs would be rolled back or struck down in court should temper expectations. Even when legal challenges arise, the U.S. administration has other avenues to keep tariffs in force. For example, on May 28, 2025, the U.S. Court of International Trade briefly blocked the emergency tariffs imposed by the Trump administration back in February 2025. These tariffs, also called the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) were enacted via an Executive Order as part of the America First Trade Policy. But the very next day, the administration obtained a stay from the Court of Appeals, effectively keeping the tariffs in place. Tariffs have become a fixture of U.S. trade policy, backed by bipartisan political pressure to appear tough on trade imbalances and supply-chain security.

Merchants should plan for a future where a baseline import tariff of at least 10% is standard on all goods, regardless of origin. And if you source from China, the effective tariff rate can be far higher. Various overlapping duties – from the original Section 301 tariffs (25%) on Chinese goods, to the additional 20% “fentanyl” tariffs added via IEEPA – stack on top of the normal import duty. The cumulative impact is substantial: a basic apparel item from China may incur well over 50-70% in total duties when all layers are applied.

Questionable Workarounds and the Crackdown on Evasion

Faced with rising costs, many brands have been scrambling for creative ways to avoid or lessen duties. Unfortunately, many “workarounds” being promoted are legally questionable or outright noncompliant. These tactics include undervaluing shipments, misclassifying goods under incorrect tariff codes, hiding product costs under multiple invoices, and transshipping products through third countries to disguise their origin. Such practices not only violate customs regulations but also expose businesses to significant legal risks. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) are intensifying enforcement efforts, utilizing laws like the False Claims Act to penalize violators. Companies caught engaging in these schemes may face hefty fines, reputational damage, and even criminal charges.

How you declare the value of your goods to U.S. Customs directly determines the duties and tariffs owed – and it’s the first area enforcement officials examine for fraud. Accurate, substantiated valuation is the foundation of customs compliance. Even as you seek to minimize costs, it must be done through the permitted valuation methods, not by arbitrarily understating the price paid. The good news is that there are lawful, compliant ways to manage costs and mitigate tariffs without violating the law.

The Foundation of Compliance: Proper Customs Valuation

One of the most challenging things to understand is customs valuation. The rules are complex, nuanced, and particular to each market. While most developed countries follow the WTO agreement on customs valuation, there are very important differences. For example, the U.S. permits the use of the “first sale” price—i.e., an earlier sale in a multi-tiered transaction—as the declared transaction value, provided very distinct conditions are met. In contrast, the UK and EU require importers to declare the value of the last sale occurring immediately before importation. This 2016 clarification by the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) effectively closed the door on “first sale” valuation in the EU.

Where nearly all countries agree is that Transaction Value is the primary method for customs valuation. This is the price actually paid or payable for the goods with certain required adjustments. These adjustments include any selling commission or brokerage paid, packing and container costs, the value of any assists (such as tools, components, or design work the buyer provided to the factory at no charge), any royalties or license fees related to the sale, and any proceeds the seller will get from a later resale of the goods. All these elements should be factored into the declared value. Conversely, certain costs incurred after importation – like domestic transport or installation – can be excluded from the transaction value.

However, the U.S. has strict criteria for what counts as a sale for transaction value. If any of these cannot be met, the merchant has to use a different, often higher, declared value:

There must be a bona fide sale: CBP defines a sale as a transfer of ownership in exchange for “consideration” or payment. This isn’t just a financial transaction—it requires actual passage of title and risk of loss to the U.S. buyer. Informal arrangements, consignment, or revenue-sharing don’t qualify.

There must be a true buyer and seller: The buyer must be a real entity—not just a paper company or middleman—and must have the authority to order goods, pay independently, take title, and bear risk. CBP expects documentation like purchase orders, commercial invoices, proof of payment, and Incoterms to prove this.

The sale must be “for exportation to the U.S.”: The transaction used for valuation must be the sale that caused the goods to be exported to the U.S. CBP considers whether the sale declared is the one that actually caused the exportation to the U.S. by looking at whether the merchandise was “clearly destined” for the U.S. at the time of that sale. This qualification is especially important if goods are drop shipped or trans-shipped to U.S. consumers or if the merchant is claiming an intercompany transfer price (more on transfer pricing below).

If transaction value is not acceptable, importers must move to the next of the six valuation methods in order:

- Transaction value of the imported goods – as described above, the actual price paid or payable, plus required additions.

- Transaction value of identical goods – the value based on identical merchandise sold to the U.S. at or about the same time.

- Transaction value of similar goods – the value of similar (not identical but comparable) merchandise sold to the U.S. around the same time.

- Deductive value – a downstream approach, based on the price of the imported goods (or identical/similar goods) when sold in the U.S. to an unrelated buyer, minus certain deductions (commissions, profit, domestic costs, etc.). In simpler terms, customs works backward from the U.S. retail price to estimate the import value.

- Computed value – a built-up approach, where the customs value is computed from the cost of production (materials, fabrication, other processing costs), plus an amount for profit and general expenses for similar goods. This method requires detailed cost data from the manufacturer and is used rarely, as it can be quite invasive.

- Fallback method – if none of the above methods can be applied, a reasonable fallback method may be used, based on the general principles of the customs valuation agreement. This cannot be a free-for-all; it must rely on previously determined values and cannot use prohibited bases (like the price in the export country’s domestic market, arbitrary minimums, etc.).

For most e-commerce brands, you will be dealing with Transaction Value in almost all cases, as you are selling goods for export to the U.S. The key is to declare the true price you paid and include all the required cost elements. Keep documentation (invoices, contracts, proof of payments, etc.) to back it up, because Customs has the right to question any value. And with the ability to look up the retail price online in a matter of seconds, it is easy for them to find values that seem abnormally low. If they suspect your declared value is not realistic – for instance, if a $200 designer shoe is declared as $20 – they can reject transaction value and “advance” the declared value to that of the retail price and the burden is on the merchant to dispute this value. It’s far better to get the valuation right upfront than to face audits or FCA investigations later for undervaluation.

Tariff Mitigation vs. Tariff Evasion

It’s important to distinguish mitigating tariffs from evading tariffs. Mitigation means finding legal, compliant ways to reduce the impact of duties; evasion means breaking the law to avoid them altogether. There are legitimate strategies to mitigate tariff costs that merchants can and should explore. These approaches adhere to customs laws (valuation rules in particular) while still lowering the duty paid. Below we outline a few compliant strategies being used by savvy brands. Each requires proper execution and comes with pros and cons, but none of them involves hiding information or deceiving authorities.

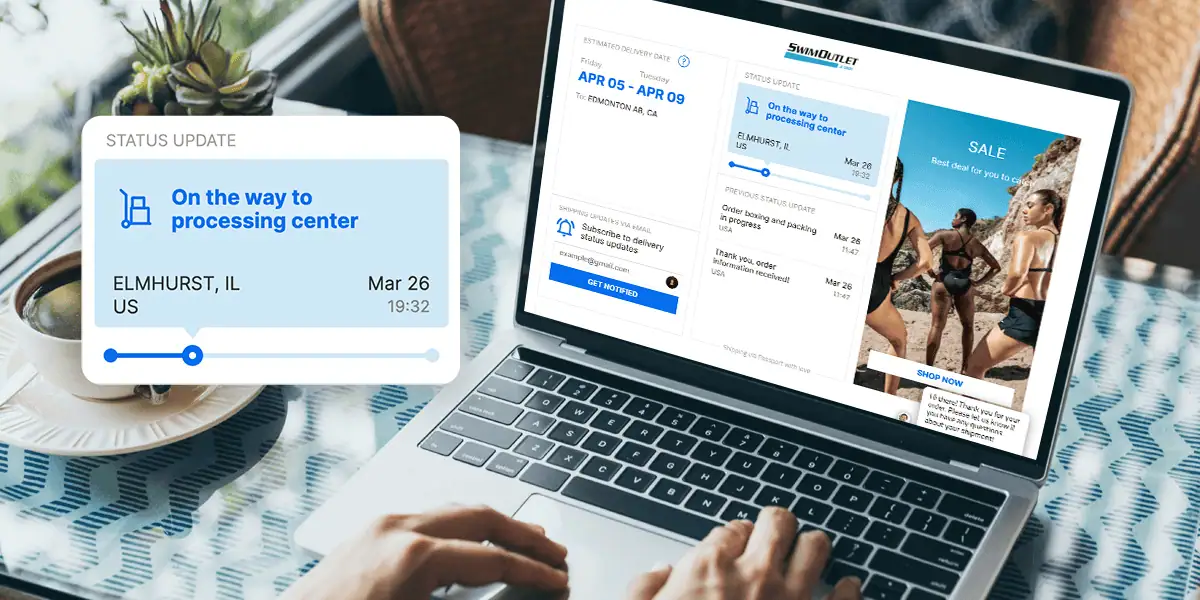

In-Country Fulfillment (ICF): This strategy involves forward-stocking your inventory in the U.S. before the final sale to the customer. Rather than shipping individual orders from overseas to U.S. shoppers (and now having each subject to duties), the merchant imports a bulk shipment of unsold goods into the U.S., then fulfills orders domestically. The big benefit is a lower declared import value based on your cost of goods. When you import unsold inventory, the customs value is typically the wholesale, transfer price or the manufacturing cost inclusive of freight charges – often much lower than the eventual retail price you charge consumers. This legitimately shrinks the duty base (since duty is assessed on the cost you paid your supplier, not the higher price your customer pays). Additionally, in-country fulfillment yields faster shipping times and better customer experience for U.S. buyers, easier domestic returns handling, and the ability to list products on U.S. marketplaces as a local seller. ICF requires significant pre-planning. Listing the most important here: (1) You as the merchant will need proper inventory planning to determine which SKUs and quantities to forward stock in the U.S based on sales forecasts; (2) you must handle the import logistics, often via ocean or air freight and bear the inventory risk (stocking products that haven’t been sold yet) and lastly (3) you’ll require a U.S. importer of record (which can be your own U.S. entity or a service provider) to handle customs entries and compliance. Still, ICF is emerging as a proven, compliant model for growing brands – one industry expert calls it “the most tested and compliant model available today.” Many Canadian, UK/EU brands are finding that the improved delivery speed and tariff savings outweigh the costs of operating a U.S. warehouse presence.

Intercompany Transfer: Some larger brands pursue a B2B2C model, setting up their own U.S. subsidiary or related company to import and distribute the products, rather than selling directly to U.S. consumers from overseas. In this model, the non U.S. parent company sells the goods to the U.S. subsidiary at an arm’s length “transfer price”, and the U.S. subsidiary then sells to the end consumer. If done properly, the transfer price for the import can be lower than the final consumer price, meaning duties are paid on a lower value. However, this approach is complex and not to be taken lightly. The U.S. subsidiary as the importing entity must be a real business with substantive operations (employees, offices, accounting records) – it’s not as simple as opening a shell LLC in Delaware. Customs closely scrutinizes related-party transactions; you have to prove the intercompany price is not artificially low to evade duty (either by showing it’s negotiated like with an independent buyer, or by comparing to test values). Moreover, funds can get “stuck” in the U.S. entity due to profit repatriation rules, and transfer pricing in tax law can also come into play. The model requires significant compliance work and has a high audit risk if misused. Only consider this if you truly plan to establish a U.S. presence and have expert tax and customs advisors to set it up correctly. For most small-midsize brands, a full intercompany structure may be overkill relative to the benefit.

Ready to future-proof your international shipping? Passport is here to help you navigate these complexities, ensuring your U.S. market entry remains profitable, compliant, and worry-free.

Want to learn more? Watch our webinar recorded on Friday, May 16th, as we explore the impacts of the de minimis change and how brands can compliantly mitigate impacts. Watch here.

Want to discuss potential solutions? Reach out to Neoshi Chhadva, General Manager of U.S. Solutions, neoshi@passportglobal.com.

This article is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Merchants are advised to consult with their customs broker and legal counsel to ensure compliance with all applicable laws and regulations based on their specific circumstances.

Authored by Thomas Taggart

Head of Global Trade | Passport

Thomas Taggart is a cross-border commerce leader with more than 20 years of experience in international shipping and regulatory affairs. As the Head of Global Trade, Thomas helps ecommerce brands go global by simplifying international trade, tax, and product compliance issues. Prior to Passport, he brought international shipping solutions to market through multiple roles in UPS’s product development organization.